This 8.7 Million Year Old Skull Didn’t Show Up In Africa. Credit: Shutterstock | Indian Defence Review

A stunning fossil find in Türkiye could upend everything we thought we knew about where humans come from. Buried for nearly nine million years, this ancient skull is forcing scientists to rethink the origins of our species.

Evelyn Hart

Published on December 31, 2025

In the high plains of central Türkiye, scientists have recovered a fossil that may hold new clues to the origins of the human lineage. The specimen, a partial skull found near the town of Çankırı, comes from a previously unknown species of ancient ape. It was preserved in sediments dated to 8.7 million years ago.

The find stands out for its condition and age. Much of the facial skeleton and part of the braincase are intact, offering rare insight into a period of human evolution that remains poorly understood. The fossil was recovered at a well-studied site called Çorakyerler, which has produced thousands of vertebrate remains from the late Miocene epoch.

Excavation of the fossil, a significantly well-preserved partial cranium uncovered at the Çorakyerler fossil site in Türkiye in 2015. Credit: Ayla Sevim-Erol

Researchers involved in the study say this fossil could belong to one of the earliest known hominines. That group includes humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and their extinct ancestors. If confirmed, the discovery would raise new questions about where and how the hominine lineage first developed.

Rather than pointing squarely to Africa, as many previous fossil finds have done, this evidence suggests an alternative view. The early stages of human ancestry may have also unfolded in parts of Europe.

A New Species From the Eastern Mediterranean

The species has been named Anadoluvius turkae. It is described in a peer-reviewed study published in Communications Biology by an international research team led by Professor Ayla Sevim Erol from Ankara University and Professor David Begun from the University of Toronto.

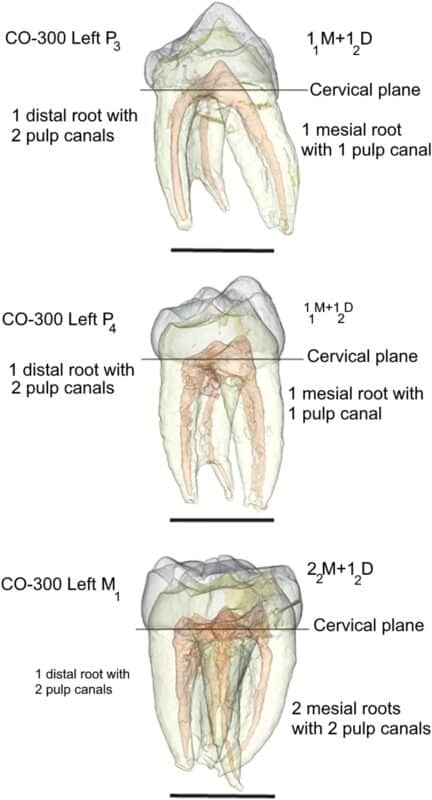

The skull was discovered in 2015 and includes the face, upper jaw and parts of the cranial vault. It is more complete than most other ape fossils of the same period. Using digital reconstructions and comparative anatomy, the researchers analysed over 100 anatomical features to determine where Anadoluvius fits in the great ape family tree.

A new face and partial brain case of Anadoluvius turkae, a fossil hominine—the group that includes African apes and humans—from the Çorakyerler fossil site located in Central Anatolia, Türkiye. Credit: Communications Biology

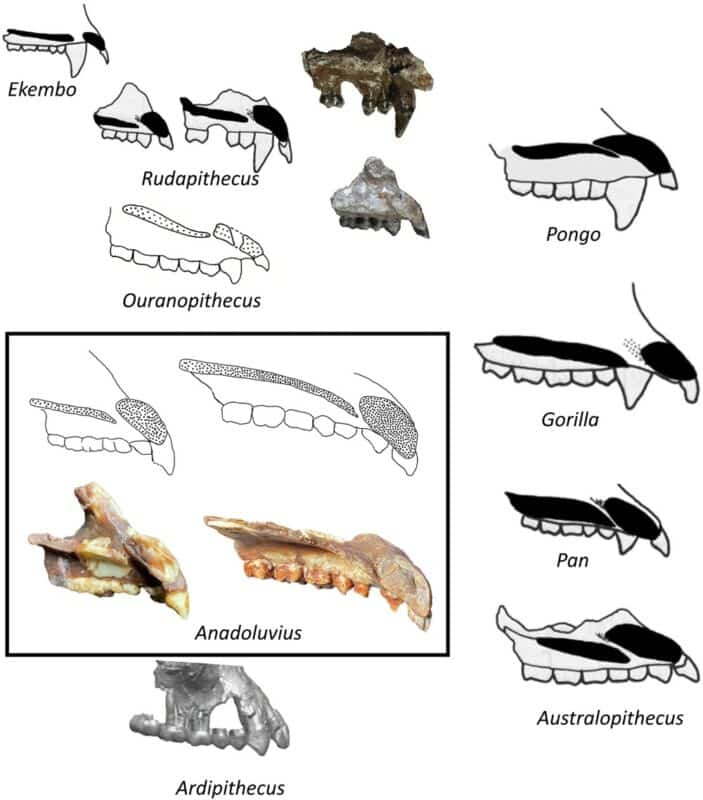

Their results suggest it belongs to the hominine group. Several characteristics support this view. These include thick tooth enamel, reduced canine size, and a short, robust face. Such features are commonly found in early human ancestors and suggest adaptations to a tough, ground-based diet.

The estimated body size of Anadoluvius is comparable to a modern chimpanzee. Its facial structure shows similarities to other fossil apes from Europe, including Ouranopithecus from Greece and Graecopithecus from Bulgaria.

Hints of an Earlier Evolutionary Path

Previous fossil finds in the Balkans had already raised the possibility that hominines were present in Europe during the late Miocene. However, most of those specimens were incomplete or difficult to interpret. The new skull from Türkiye provides clearer evidence and allowed the researchers to build a more detailed evolutionary model.

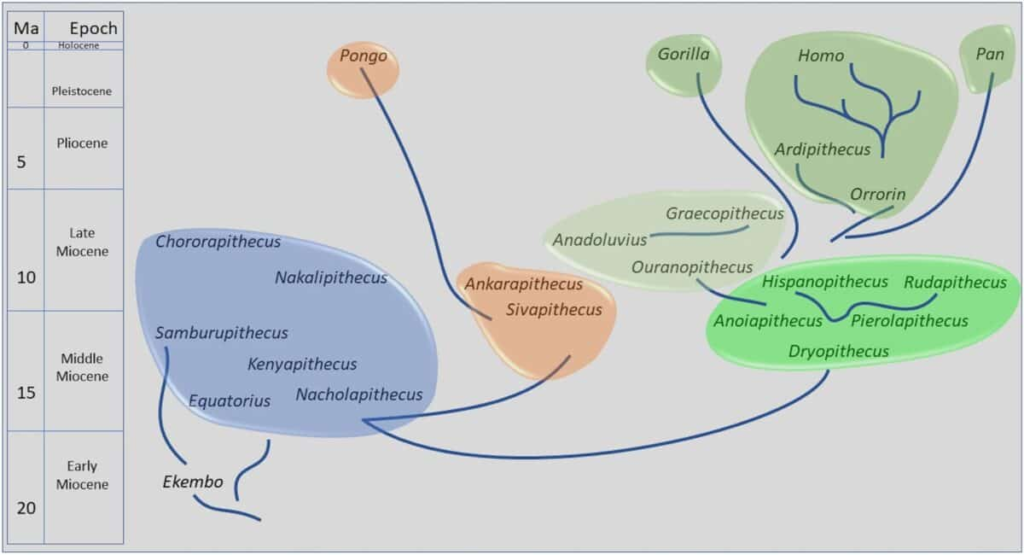

The study’s phylogenetic analysis places Anadoluvius, Ouranopithecus and Graecopithecus in a clade with modern African apes and humans. This group is distinct from Asian great apes such as orangutans, which belong to a separate lineage called pongines.

Cross sectional anatomy of the palate in Anadoluvius and other hominids (not to scale). Credit: Communications Biology

“The members of this radiation to which Anadoluvius turkae belongs are currently only identified in Europe and Anatolia,” said Begun. He added that these apes likely evolved from ancestors in western and central Europe, then spread to the eastern Mediterranean.

No fossils of hominines have been found in Africa that are older than seven million years. In contrast, the European fossils span a period from roughly 9.6 to 7.2 million years ago. This has led some researchers to suggest that hominines may have first evolved in Europe before migrating to Africa.

Adapted to Dry, Open Environments

The environment in which Anadoluvius lived was not tropical forest, but rather dry woodland and open grassland. This interpretation comes from both the fossil’s anatomy and the animal species found at the Çorakyerler site.

Faunal remains from the area include giraffes, zebras, elephants, antelopes, porcupines and large carnivores. This suggests a landscape more like modern African savannas than the forested regions inhabited by most modern apes.

3-D reconstruction of the left P3 to M1 of CO 300, showing the root, root canal and pulp chamber configurations. Credit: Communications Biology

“Judging from its jaws and teeth, the animals found alongside it, and the geological indicators of the environment, Anadoluvius probably lived in relatively open conditions,” said Sevim Erol. The researchers believe it likely spent time on the ground rather than in trees, based on its dental features and body size, although no limb bones have yet been recovered to confirm this.

The ape’s powerful jaws and thick enamel would have been useful for processing tough or gritty foods, such as roots and tubers, which are more common in open environments.

Rethinking the origin of hominines

The discovery adds new data to a longstanding debate in human evolutionary biology. For decades, most scientists have believed that the hominine lineage originated in Africa, based on fossil finds and genetic evidence. That view remains dominant, especially for later stages of evolution including the emergence of Homo sapiens.

However, the age and location of Anadoluvius turkae suggest that earlier evolutionary steps may have taken place in Europe. This would mean that hominines evolved in Europe, diversified, and then dispersed into Africa sometime between nine and seven million years ago.

A phylogeny of the taxa included in this analysis consistent with most of the cladograms presented here. Credit:

“The remains of early hominins are abundant in Europe and Anatolia, but they are completely absent from Africa until the first hominin appeared there about seven million years ago,” the study states.

Researchers caution that the case is not closed. More fossils from both Europe and Africa, especially from the same time period, will be needed to confirm or challenge this hypothesis. The authors stress that this find does not replace the African origin theory but adds a new dimension to it.

Original:https://indiandefencereview.com/fossil-evidence-europe-human-origins-not-africa/